Park visionaries | The Madison Parks Foundation

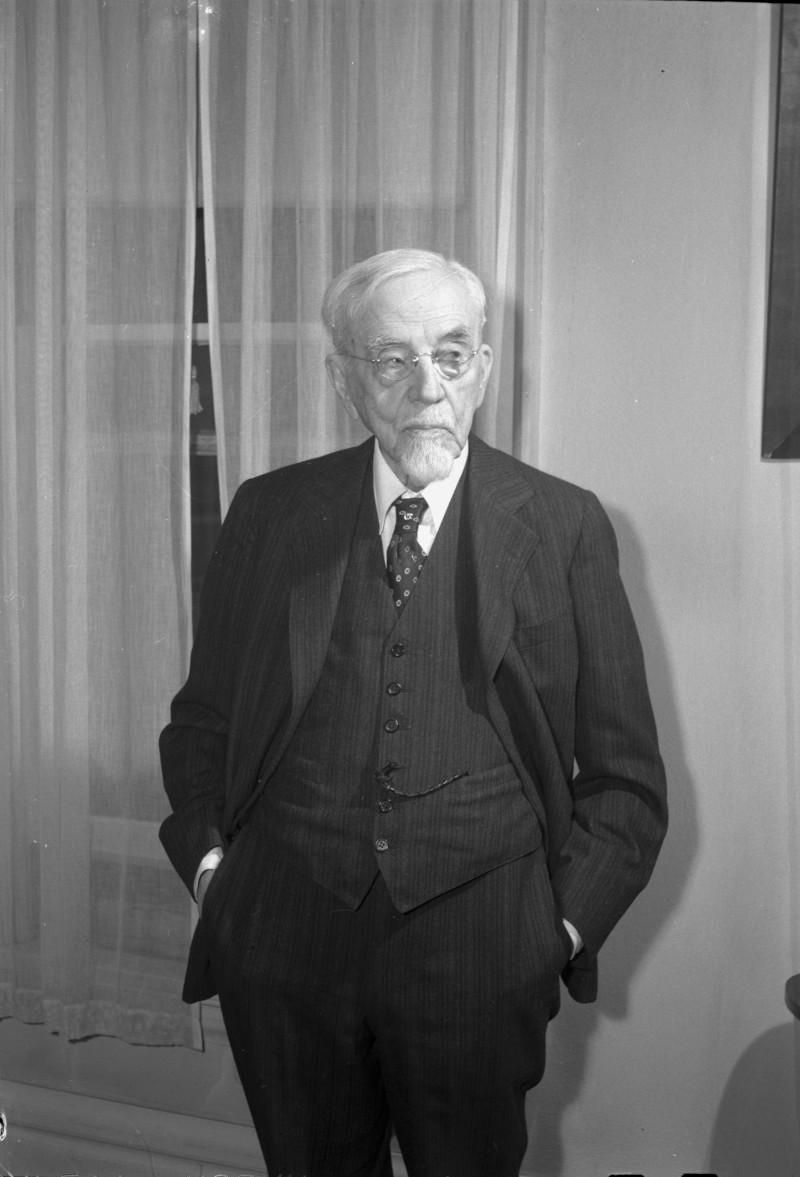

John M. Olin (1851 – 1924)

John Olin is considered the father of the Madison Parks system. He was a leading entrepreneur, conservationist, and philanthropist. His innovation paved the way for the parks that we have today.

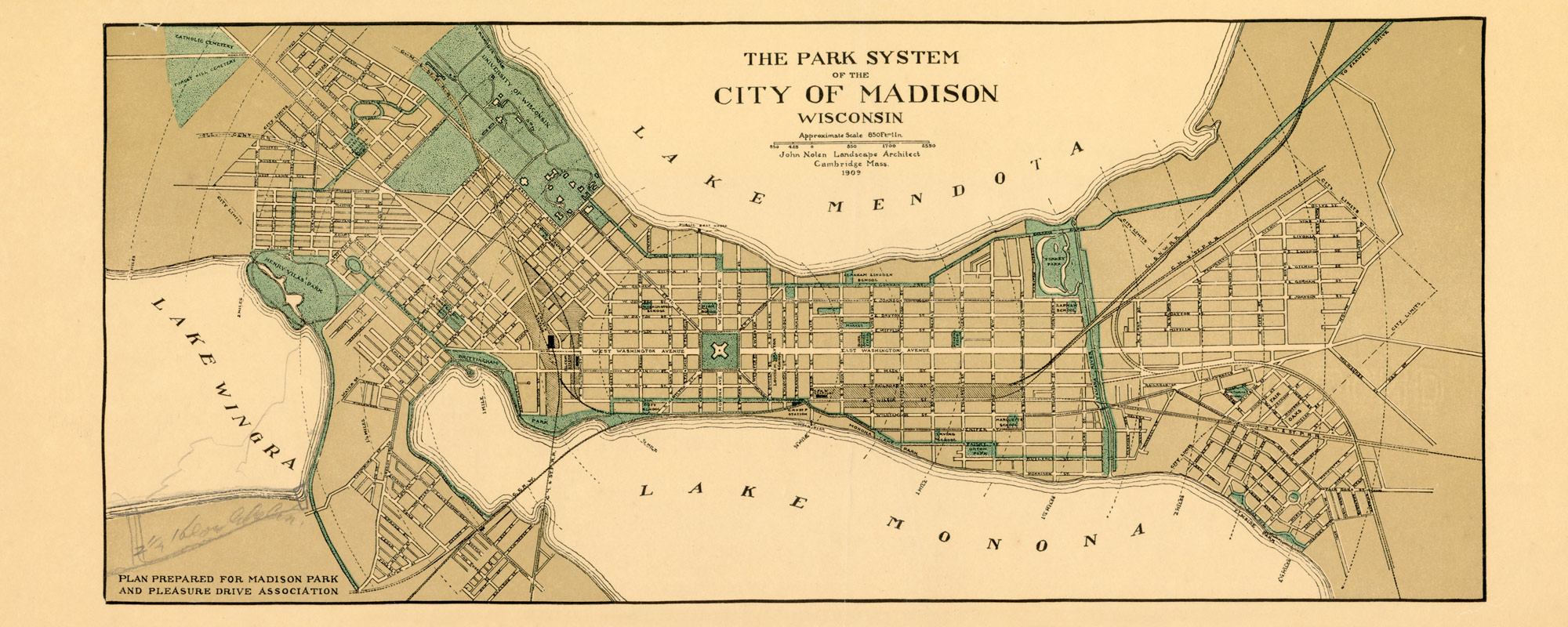

Between 1894 and 1909, Olin was the first president and propeller of the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA). The MPPDA began with just 3.5 acres of parkland with no park commission. By 1909, Olin established 269 acres of parkland, a park commission, and a “park-building” organization; he persuaded community members to contribute over a quarter of a million dollars to the development and maintenance of the parks.1

Thanks to John Olin and the legacy he created and left, today there are 279 Madison Parks which includes nearly 6,000 acres of park land.

*Mollenhoff, David V., Madison: A History of the Formative Years (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1982), 231

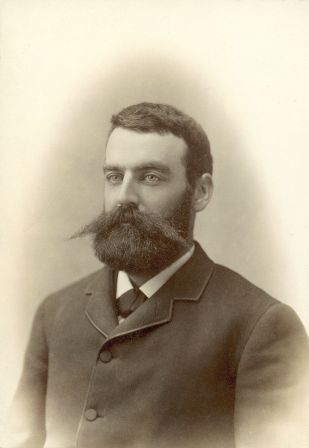

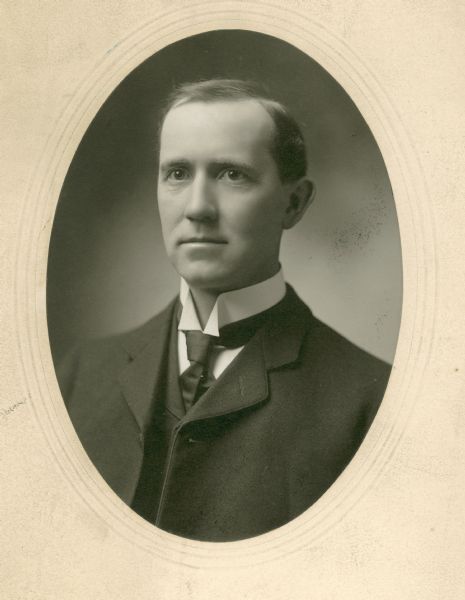

Edward T. Owen (1850 – 1931)

In April 1892, UW Professor Edward Owen began work on creating the Madison Park & Pleasure Drive Association and enlisted John Olin to work with him. At this point, there were no parks, pleasure drives or lakeshore areas available for public use in the Madison area with the exception of Orton Park, which was previously the City’s cemetery.

Owen purchased 14 acres for park & pleasure drive purposes (extending from the northeast corner of the Catholic cemetery west through the William Larkin Farm around Sunset Point, the dividing into 2 drives – one continuing to Mineral Point Road and the other proceeding North to University Avenue.) for $3,000 which included the improvements to that land. This is now known as Hoyt Overlook.

Owen and Olin obtained easements and contributions to create a causeway across University Avenue – known as Willow Drive. The creation Willow Drive and a gift from Edward Hammersley and a citizens group, a drive was established connecting Observatory Drive with Raymer Road (Eagle Heights Road, later Lake Mendota Drive) in addition to reconstructing the Rustic Bridge. Opening in October, this connection became the first scenic or pleasure drive – University Avenue to (present-day) Capital Avenue. It was a huge success opening to 70 carriages that made the 3-hour drive.

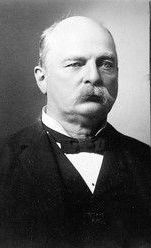

Daniel Kent Tenney (1834 – 1915)

Daniel Tenney was an important figure in Madison’s development and growth, both politically and financially. Tenney is considered one of Madison’s first park philanthropists, along with Thomas E. Brittingham, George B. Burrows, and William Freeman Vilas. Tenney’s contributions to the city of Madison helped shape it into the great park city it is today.

Tenney was a lawyer, long-time activist, and “Madison’s favorite curmudgeon.” Elected to the Madison Common Council in 1860, Tenney was the youngest man to ever serve on the council at the age of 26. In 1899, Tenney bought fourteen acres of land near Lake Mendota for $1,500 and offered to give another $2,500 for the development of the land as a park. This donation, however, came with some conditions. First, MPPDA would hold the land in trust for the city. Second, the association would develop and maintain the park. Third, another $2,500 would be raised for park development from other sources. MPPDA agreed and development of the park began in 1900. The donation helped the MPPDA switch its gears to begin focusing on expanding in-city parks for the less affluent. The city council dubbed this park Tenney Park.

*Mollenhoff, David V., Madison: A History of the Formative Years (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1982), 326-328

William Freeman Vilas (1840 -1908)

William’s parents moved to Madison, Wisconsin when he was a small child. Vilas was admitted to the Wisconsin bar upon graduation, the outbreak of the Civil War led him to volunteer in the Union Army; he eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel. At the end of the war, he returned to Wisconsin to practice law, and in 1868, he became a professor of law at the University of Wisconsin.

President Cleveland nominated Vilas to become secretary of the Interior and also served as the first Postmaster General. In 1891, the Wisconsin legislature elected Vilas to the U.S. Senate, where he served until 1897. Vilas then became a regent of the University of Wisconsin in 1898. Vilas also served as one of the members of the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association.

In 1904, the City of Madison received 50 acres of land from William and Anna Vilas under the conditions that it be used “for the uses and purposes of a public park and pleasure ground”. The park was named in honor of the Vilas’s son, Henry, who died at a young age from complications related to diabetes. The family stipulated that the park always be admission free. In 1911, 28 acres of the park were partitioned into an animal exhibit, now known as the Vilas Zoo.

Thomas E. Brittingham (1860-1924)

Reportedly Madison’s richest man, was incredibly generous with his riches, especially to Madison’s parks. His assets included 126 lumber yards, thousands of acres of standing timber all over the country, oil wells and large interests in financial institutions. His philanthropy to the city of Madison earned him the title of one of Madison’s first park philanthropists.

Extremely involved in the community, Brittingham was chairmen on the Forest Hills Cemetery Committee from 1907-1912, curator for the Wisconsin Historical Society from 1907-1913, chairmen of the State Park Board from 1909-1918, and UW Regent from 1910-1912.

Brittingham’s contribution to Madison’ parks came in the form of $19,500 donation to transform “a stinking slough into a beauty spot”, which is now known as Brittingham Park. Between 1905 and 1908 Brittingham gave a total of $24,500 for the improvement of this area, providing the city with its first park with water access. Brittingham Park offered an expansive beach, a boathouse, a waterslide, and rental swimsuits. Nearly 50,000 swam there the year it opened.

*Mollenhoff, David V., Madison: A History of the Formative Years (Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1982)

Frank W. Hoyt (1852 – 1950)

A successful banker and an advocate of parks; Hoyt was instrumental in establishing the UW Arboretum in what was known as the Hoyt Transfer – a land transfer deal. Between 1894 and 1934, Frank W. Hoyt acted as a leader in the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association serving as the Treasurer from 1916 to 1929.

The origins of present-day Hoyt Park can be traced to 1890 when the City acquired property rights to twenty-four acres of a stone quarry which in time grew to its current thirty-one acres through donation and purchase. By 1933, operations at the stone quarry had ceased and the land had officially become a city park when it was named Hoyt Park in honor of Frank W. Hoyt also known as “The Grand Old Man.”

Ernest N. Warner (1868 – 1930)

In 1889, Warner graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Madison witha degree in modern classics. He then attended the university’s law school and completed his law degree in 1892. Warner served in the 1905 State Assembly where he successfully introduced landmark civil service.

In 1912, Warner became the president of the Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA) and was later appointed to a committee of the MPPPDA to acquire a beach for the public. Tragically, Warner was killed in an automobile accident. Within two weeks of death, the Ernest N. Warner Memorial Park Committee was formed to raise $20,000 to purchase the beach in his honor*.

*”Plan $20,000 Park to Honor Warner,” Capital Times, July 22, 1930

Michael Balthazar Olbrich (1881-1929)

Michael Olbrich moved to Wisconsin from McHenry County, Illinois in 1989 to attend the University of Wisconsin-Madison at the young age of 17. He was a great debater and graduated from law school in 1905. Olbrich served as the deputy attorney general of Wisconsin from 1919 to 1921. He also opened his own successful law firm and served as a UW Regent.

Olbrich was deeply influenced by the example of another Madison attorney, John M. Olin, the longtime president of the nationally known Madison Park and Pleasure Drive Association (MPPDA), the private organization that created Madison’s outstanding park system. He was a long-time member of the MPPDA and even served as their president. In 1916, Olbrich envisions a park and flower garden and in 1920 he invites landscape O.C. Simonds to create a plan for the development of this park, now known as Olbrich Botanical Gardens. Between 1921 and 1922, he purchases land along Lake Monona shoreline now known as Olbrich Park. Olbrich was also instrumental in acquiring the land for UW Madison Arboretum.

In Olin, Olbrich found both inspiration and a perfect model for living a life that united a career in law with a passion for social betterment and a love of the natural world.

Oscar Rennebohm (1889-1968)

Oscar Rennebohm graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1911, after which he worked as a pharmacist and in 1912 he founded Rennebohm Drug Stores. He was vice-president of the American Pharmaceutical Association and president of the Wisconsin Pharmaceutical Association.

Rennebohm became governor in 1947 when Governor Samuel Goodland died in office and won the office outright in 1948. In 1949, he founded the Rennebohm Foundation, which supports education in the Madison area. In 1952 Governor Walter Kohler named Rennebohm to the UW Board of Regents.

Rennebohm was instrumental in sale of the University farms with land donated to the City of Madison for parks, land allocated for a state office building and eventually the Hilldale Shopping Center, residential lots sold for more than $5 million and placed more than $40 million on city and county tax rolls. There is now a park named in his memory in the Hill Farms area and the school of pharmacy at the University of Wisconsin–Madison is named after him.

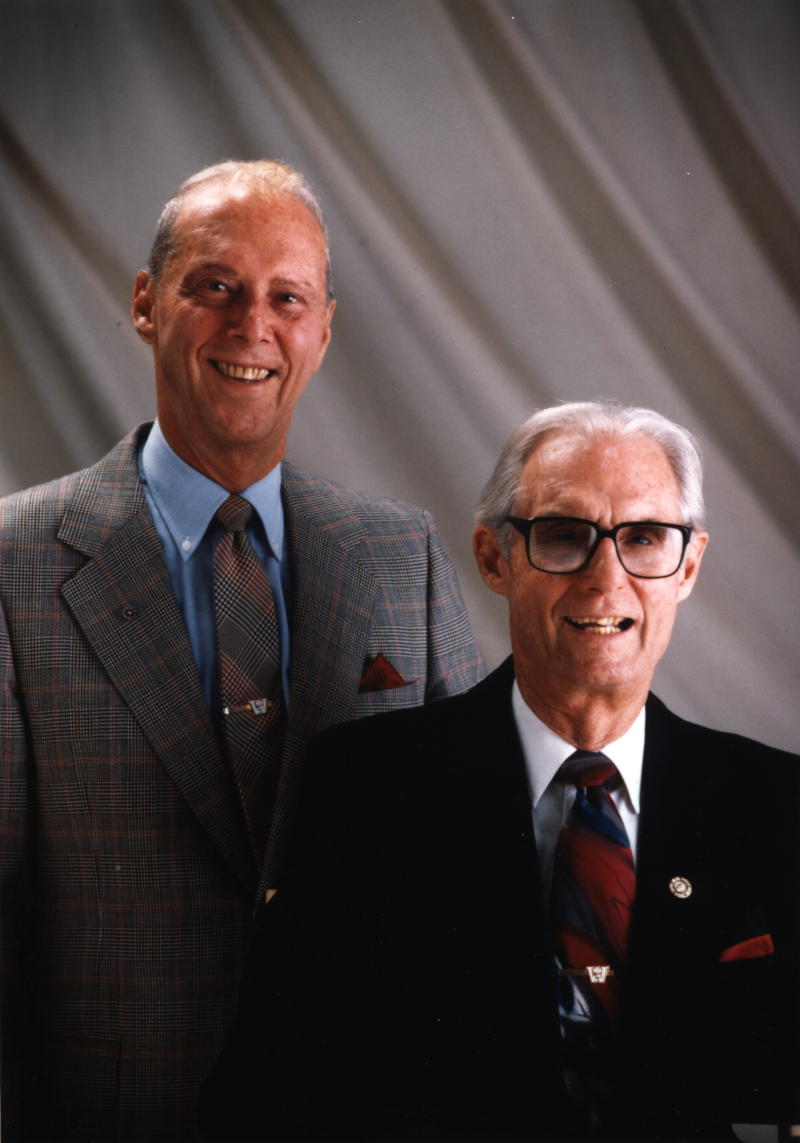

The Goodman Brothers

Irwin Goodman (1915-2009) to Madison in 1937 to operate a family jewelry store. A celebrated baseball player at UW–Madison, Robert (Bob) (1920-2010) joined his brother soon after and the two enjoyed careers that spanned more than sixty years. After establishing their business, Irwin and Bob began to look for ways to give back to the community. They gave for more than seventy years and Madison parks have been a beneficiary of the Goodman’s philanthropy thanks to the brothers’ commitment to public recreation spaces and activities. Their $2.8 million lead gift to construct a city swimming pool jumpstarted the project and now carries their names. The Goodman brothers didn’t stop there; they went on to establish a pool scholarship fund, which is administered through the Madison Parks Foundation providing free swimming lessons and pool passes to disadvantaged children and their families.

The Goodman Foundation ensures that the brothers’ philanthropy will live on through its mission “to preserve and enhance the legacy of Irwin and Bob Goodman in Madison, Wisconsin.”

Mention the Goodman brothers and their legendary generosity to most Madisonians, and they will nod their heads knowingly. From the Goodman Pool to the Goodman Campus to the Goodman Community Center, the brothers’ stamp on who we are and what we stand for as a community sends a loud and clear message that to them, Madison was so much more than a place to conduct business.